Watercolor by Daniel LaCroix

“I always tried to envision getting good people to make democracy work. I didn’t want to confine myself with wilderness.”

Stewart M. Brandborg, Executive Director, Wilderness Society, 1964-1976

Stewart Brandborg, the last true activist to lead The Wilderness Society, maybe the oldest activist still fighting the Wild West’s crazy resource wars, maybe the last old-time activist left in America, was sitting in his motorized wheelchair, telling a story.

One time his friend, Olaus Murie, had come to Washington D.C. on a Greyhound bus from his cabin in Moose, Wyoming to testify before Congress on behalf of some critical conservation issue or other. Olaus was president of a small organization (The Wilderness Society) on the cusp of blooming into its name, and this was the late fifties, the golden age of massive federal projects that were by design and definition bigger and more durable than the pyramids of ancient Egypt. It was the golden age of dams.

Congress, like Egyptian monarchies, is one of those rarified clubs that attracts vulnerable people who, as often happens, accumulate more power than they can handle and become prone to the suffering of pharaohs. This is a diagnosable disease, a timeless itch that has everlastingly tanked societies grown too top-heavy. It’s the itch of would-be gods who worship themselves and the big and durable things they could command to be built in their names and then have those big things named after them. So, although Brandy couldn’t recall the exact nature of his friend’s visit when he picked him up at the bus station that day, it was probably a dam that Olaus had come to town to school the pharaohs about.

A long trip on a bus back then took some wind out of your sails even if you were young, but especially when you were in your sixties and dealing with health issues, as Olaus was. So when the bus pulled into the station, Olaus, who had logged thousands of miles on foot and dogsled in the mountains of Alaska and Wyoming, took a walk around the block to stretch his legs while waiting for his ride.

Olaus and Brandy had a lot in common. Both were westerners, uncomfortable in cities and physically-acclimated to living outdoors. Both were wildlife biologists with extensive experience “in the field”. Finally, and maybe most importantly, both came from that pioneer strain of Scandinavian stock that still populates the North-Central Minnesota plains, the people who came immediately after those plains were seized from the Dakota people during the tense, uncertain early years of America’s Civil War. It’s ironic that these lands were taken during the watch of no less a politician than Abraham Lincoln, who would seek to secure the blessings of liberty for immigrants fleeing tyrants in Europe and for people from Africa whom those Europeans enslaved, but couldn’t seek the same courtesies for the original inhabitants of the Land. True, there were sentimentalists among the abolitionists who elevated him to the presidency, who yearned to “save” the “savage” with “Christianity”, none of which were words used by the Dakota people to describe themselves or their predicament. For his part, Lincoln also used words alien to the Dakota people, to describe what his administration took from them. He used the words like “frontier” and "wilderness" and, given the radical strain of Swedes and Norwegians that ended up springing from that virgin sod of the Dakota peoples’ plains turned upside-down, that’s a pretty fair definition of irony. What, for instance, could late-19thcentury Scandinavian farmers fleeing decrepit, autocratic monarchies in search of personal freedoms have known about what the Dakota People thought of their dear Land, or how they described it?

Not much really, and so the Scandanavian farmers didn’t think about it much, at least not at first, and that’s how it was when Olaus was born in 1889 along the Red River that defines the boundary between North Dakota and Minnesota, to Norwegian immigrants and, four years later, when Brandy’s father, Guy (also known as “Brandy” throughout his lifetime) was born in Ottertail County, the next one over from the Muries, to Swedish stock.

By the mid-1950s, Guy’s son, Stewart, and Olaus were fellow Wilderness Society board members. Brandy’s day-job was Project Director for the National Wildlife Federation, whose director, George Callison, saw potential in bringing “westerners” into the simmering national conservation stewpot, westerners who liked to fight dams, which was exactly what Brandy was doing in central Idaho when Callison became aware of him. There were two massive federal dam projects proposed to drown out Central Idaho’s wilderness, Penny Cliffs on the Middle Fork of the Clearwater and Bruces Eddy (later realized as Dworjak Dam) on the North Fork, and Brandy was fighting both of them while simultaneously working for Idaho Fish and Game, an impressive juggling act. He had been a lookout and a smoke chaser for the Forest Service in his teens and had studied mountain goats for several years during and after college. He was a wildlife biologist, a conservation activist, the son of an already-iconic “social forester” of the Gifford Pinchot mold, and a westerner. It was a novel idea, this seeking out those who lived in the “field” and who could speak in eloquent counter-arguments to nominally-elected potentates openly pining for their own monogramed Eighth Wonder and Callison set his sights on enticing Stewart Brandborg to come to Washington. And so he did.

It wasn’t long after the Brandborgs, Stewart, AnnaVee and their baby, Becky, had settled into the rhythms of D.C. that Howard Zahnizer, executive director of The Wilderness Society, noted similar potential in this big, young, talkative westerner. “Zahnie” took Brandy under his wing, drove him around Washington D.C. in his Cadillac Convertible (which ever-after impressed Brandy as “the bee’s knees”) and tapped him to serve as a board member of the Wilderness Society, as a protégé and also as a taxi-driver for fellow conservationists needing rides to and from bus stations. So Brandy was not surprised when he showed up and found Olaus waiting for him, holding a leaf.

“It’s amazing,” he recalled Olaus saying. “How fine-veined they are, how they blow down the sidewalk in the wind as they do. How perfectly designed for their purpose they are.”

AnnaVee was listening to this story from their open kitchen. She had been tolerating Brandy’s telling of it until he came to the part about the leaf. Then she quietly sidled up, which was how they split the duties of lifelong activism all those years in D.C. and then in Montana--evenly. She was Brandy’s fact-checker, Brandy taking up the airspace, AnnaVee underlying his narrative with the critical combination of introspection and accurate memory.

“There are some things that you should know about Olaus, Sigurd Olson and Zahniser” she advised me in her quiet voice that was every bit as earnest as Brandy’s louder one.

“Zahnie was somebody that you just immediately loved. You just felt good in his presence. The same was true for Sig. You were glad to be there, and glad to have him with you. Olaus was a little different sort of person. To me, sitting with him was like sitting next to Christ.”

This book, “What’s Bigger Than the Land?”, was started--and partly takes place--in Stewart and AnnaVee Brandborg’s livingroom, just south of the small western-Montana town of Hamilton. Brandy was not only the last surviving architect of the 1964 Wilderness Act, he’s also been an instigator and touchstone for much of the considerable environmental activism which has occurred in Western Montana since he and AnnaVee packed it up and moved back home from the Beltway in 1986. Countless strategy meetings have occurred in this house, leading to significant victories—or at least stallings--against the local adherents of the extractive status quo, which in turn led to his and his family’s vilification by those local adherents. Brandy and Anna Vee were both native Montanans with deep roots and, since the Bitterroot Valley is still rural and relatively small, at least one of the villifiers was someone who attended their wedding in 1949. There have also been those people who just moved up from some urban dystopia with the intent of surrounding themselves with others who look like them (Montana is almost 90% white) and think like them (Trump won in Ravalli County by almost 70%). Just people, in other words, the usual problem, but no matter. Brandy and AnnaVee never gave an inch, let alone gave up. They were of that vanishing species of gracious, determined fighters who listened to everybody and then did what they knew had to be done. Liberals in the old-time sense of the word, which is to say “socialists” in the old-time sense of that abused word (at least Brandy and his dad were, although they never entered into socialism's unfortunate "dogma-wars" by describing themselves as such), rare beasts in our current, troubled times.

The topic of our first discussions were several vintage cardboard boxes of personal files from Brandy’s days as Executive Director of The Wilderness Society. The story of the boxes, in a nutshell, is about how Howard Zahniser—Brandy’s friend and mentor—unexpectedly died four months before his eight-year battle to pass a Wilderness Bill was finished. Brandy took over as head of the Society for the last push and, when Lyndon B. Johnson finally signed it into law on September 3, 1964, Brandy characteristically missed the whole thing. He was, instead, out west.

“I was the guy,” Brandy put it, “that had worked his butt off following Zahniser’s passing in May, and I didn’t even get to the signing. I regretted that but here I was with four kids and a raccoon…”

This was a pattern repeated throughout his long life (he died in 2018 at the age of 93). In the summer of 1945, for instance, he was surveying lodgepole out of Bozeman, two feet in diameter and straight as pillars holding up the roof in the sky. He had been classified 4-F by the draft board a couple years before, and his aunt had given him a Model T. On VJ Day, when the atomic age was gaping its jaws in Japan, he was in Bozeman, celebrating with a girl he liked. After all, he had a Model T.

He wasn't sure whether Johnson knew a wilderness from a cow pasture, but he was a superb politician, and that’s what mattered as far as signings go. He didn't need to be there, and so seminal events could yawn in the distance for all he cared, and that was one of the biggest gifts Brandy brought to the Wilderness Law and, more importantly to the implementing of it. Someone dedicating their life to the preservation of America’s remaining intact ecosystems needed to know the Land enough to be humbled by it, and so it was that so long as there was still some open country left to roam in, Brandy would roam in it, and encourage others to do so.

This was a pattern repeated throughout his long life (he died in 2018 at the age of 93). In the summer of 1945, for instance, he was surveying lodgepole out of Bozeman, two feet in diameter and straight as pillars holding up the roof in the sky. He had been classified 4-F by the draft board a couple years before, and his aunt had given him a Model T. On VJ Day, when the atomic age was gaping its jaws in Japan, he was in Bozeman, celebrating with a girl he liked. After all, he had a Model T.

He wasn't sure whether Johnson knew a wilderness from a cow pasture, but he was a superb politician, and that’s what mattered as far as signings go. He didn't need to be there, and so seminal events could yawn in the distance for all he cared, and that was one of the biggest gifts Brandy brought to the Wilderness Law and, more importantly to the implementing of it. Someone dedicating their life to the preservation of America’s remaining intact ecosystems needed to know the Land enough to be humbled by it, and so it was that so long as there was still some open country left to roam in, Brandy would roam in it, and encourage others to do so.

Brandy led the Societyfor the next twelve years, until 1976 when he was fired by the board. This occurred because he fought an oil pipeline in Alaska, and had alienated some industry-funded foundations such as the Mellon Foundation (Gulf Oil) that some members of the board were interested in soliciting grant money from. Brandy wasn’t being “professional” enough, these board members surmised, and so they hired a business consulting firm to find fault in Brandy’s “professionalism”, which the consulting firm dutifully did. Brandy’s firing, in turn, created an uproar throughout the environmental community, and even today to say out loud what was widely-thought back then, that The Wilderness Society fired Brandy because he spearheaded an almost-successful fight against the Alaskan Pipeline is a statement incredible on its face and still unbelievable to many within the movement. But that’s what happened, and in early January of 1976 , he and two of his top staff staff, Ernest Dickerman and Virginia (Peeps) Carney (both of whom would resign from the organization soon after), arrived at The Wilderness Society offices in downtown Washington D.C. to clean out his office. They ended up stuffing a couple dozen boxes full of Wilderness Society records covering the periods 1955 to 1977 that Brandy wanted saved—which were most of them--and walked them out through an unused back door onto the asphalt roof of the People’s Drugstore, which their offices sat above and which, coincidentally, was within sight of the White House. They didn’t use the front door because the new interim-director, Clif Merrit, a long-time colleague of theirs and a fighter in his own right, was sitting at the front desk, supposedly monitoring what Brandy was taking out of his office. The whole thing was, to say the least, awkward: for them, for the new interim-director, for everyone involved in the whole awkward affair.

They carried the boxes across the roof and down the fire-escape ladder, where the Brandborg family’s station wagon was parked on the street below. They loaded them up, and Brandy drove the boxes home to Turkey Foot Road in Maryland just north of the Washington metropolitan area, and that where they stayed for a decade, when the Brandborgs finally headed west for good.

The Wilderness Society entered into a period of turmoil from this event. It became one of the major debacles in America’s post-Nixon world, when the “left” seemed to be finding its feet and then, seemingly-inexplicably, stumbled. There was an explanation, of course, but it’s still a inexplicably-fierce debate raging within the nationwide environmental community: how beholden progressive non-profits should be to corporate donors. Brandy, who was in on the cusp of so many watershed victories for the environmental movement, was also in on the cusp of that same movement’s watershed setback from which it has never fully recovered. Nixon, who would have been in the last year of his presidency in 1976 if he hadn’t been forced to resign, could rightly claim that he had signed more environmental legislation into law than any other president. But Nixon’s green tint was almost wholly the result of the democratic pushing and shoving from below that Brandy and his colleagues were so adept at. Maybe Nixon could be excused if he snickered a bit at the whole affair because, in the end, he got his pipeline.

When the Brandborgs moved back to the Bitterroot Valley, the Wilderness Society files came with them. Still tucked in their original cardboard boxes, they were stored in the various basements, garages and sheds where papers that are dear to the possessors invariably end up, and in those vintage boxes they remained, relatively unmolested for the next thirty years.

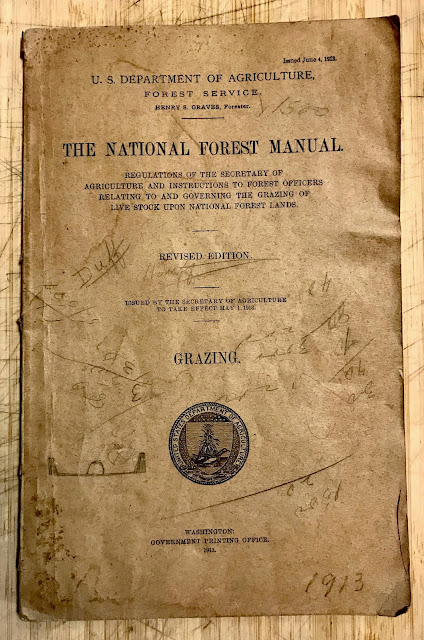

It wasn’t a complete set anymore. Some had already made their way down to the University of Montana archives in Missoula. An unspecified few had been lost in a still-unexplained house fire when the Brandborgs were living in the hills above the small logging town of Darby twenty miles south of Hamilton, a town which still held both him and his dad personally responsible for “shutting down the mills” decades ago, the very mills that both Brandborgs had repeatedly warned were overcutting their own selves out of existence—which is what they did. But through all that about a dozen boxes still remained, mostly in the garage, a few out in the garden shed. They contained dog-eared documents from the environmental movement’s budding days when so much seemed possible, and actually was achieved. There was a whole box, for example, marked “Timber Supply Act”, an existential threat to the budding power of an unpredicted awakening that was by fits and starts blooming and booming by the late sixties. If it had passed, it would have congressionally-mandated unsustainable levels of timber harvest on national forests into perpetuity, making moot most of the improvements in forest management that came before and after it. The remaining forests of the Rockies, indeed the remaining forests throughout the nation, would have been stripped for quick cash, as so many had been already. This was at the height of the Vietnam War, when college kids and their professors were widely credited with such notions as “ecology”, “wildlife corridors” and “population explosion”, notions that industrialists felt had no place in serious talk about forest management, let alone about anything else. It was all pure communism to them, but Brandy, having grown up with his feet in the actual dirt, called their bluff and made it stick, which was another of his strengths. It was his saddle-seasoned dad, after all, who was raising hell about overcutting the Bitterroot National Forest, in what came to be known as the “Clearcut Crisis” at this very historical second when such “anti-communists” as these industrialists invariably were, who may have never seen a mule up close let alone settled their butt on one for a month, were advocating for armed soldiers on college campuses as the solution to this “problem” of the sixties. The Clearcut Crisis in the Bitterroot was exactly what the sponsors of the Timber Supply Act had in mind to counter with their no-nonsense, get-the-cut-out legislation. They even gave the Brandborgs an off-hand compliment by re-naming their legislation the “National Forest Timber Conservation and Management Act” which, of course, was not about conservation at all. Stewart and Guy took them down in flames, paving the way for the National Forest Management Act of 1976, and this Brandy claimed as one of his proudest moments, a largely-forgotten one now that had a significant mouse nest in it, possibly multi-generational ones. Clearly something needed to be done.

Personal miracles exist in almost anyone’s garage. Letters from great-aunts who moved to Los Angeles to be movie stars, pictures of ancestors on Ellis Island, that $96 hospital bill that paid for your birth, the sort of documentary detritus that doesn’t want to be thrown out but transforms into clutter after a few decades of hanging around in linen closets. That’s when a time-honored trajectory is applied to them with the rationale that, if you can’t fit it neatly on a bookshelf or turn it into furniture, out it goes into the true archive of American history since at least World War Two—the garage. In the Brandborg’s case, this accumulated detritus ran deep into a largely-forgotten history, or worse a misinterpreted one, of an environmental awakening that hadn’t happened in this country before, and, sadly, hasn’t happened since. It was exciting, overwhelming and personal. Foolishly, perhaps, I dug in.

The wording in this book attributed to Brandy are either in quotes as his own, or paraphrased from his own. They can be found within the excellent series of taped interviews conducted by Dick Ellis in 2003, in several other interviews and videos now archived at the University of Montana’s K. Ross Tool Archives within the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library or within the tapes and notes of my own conversations with him (also archived--see appendix). I tried to stay faithful to his meaning and intent, while not generally citing or footnoting them overmuch along the way because I decided it would distract from the stories which I was ultimately after in the boxes—and what I believed Brandy was after, too. Not just the facts within (which, in the interest of full disclosure I admit that, due to their voluminous nature compared to my own, laid-back one, I merely cherry-picked) but the dust they kicked up. Brandy’s especially but a little of my own as well. After all, it’s been my luck to choose a drop-dead-gorgeous country like the Bitterroot to live in during such interesting times. I’ve been working and playing here for decades, in the same wild country that Brandy and his colleagues saved for my generation to have the opportunity to live, work and play in at all, and I have something to say about how they are being defined and defiled by those who simply may not know the history of their temporary salvation well enough. There’s something here in the Northern Rockies, I think, this home-sweet-home of the Nimi’ipuu (the Nez Perce People), that speaks to the existential pickle we’re in. Call it a power, a trance, radon poisoning. What I know after all these years is this: that whatever it is, it exists, just like Jesus, neither of which you can justify your belief in other than to say that most beliefs are valid if they’re honest, and that some are even true. Beliefs squishy things, after all, and necessarily so if they’re to have any value to the believer. Everyone believes something, but whatever belief you chose to bake to that golden brown that makes them edible, shouldn’t they at least be leavened with some mere observations? That any belief a society hold dear is a compromise? One that a society makes with its natural environment in order to illuminate the rules of survival so a member of that society can see the rules for what they are? That real beliefs, the useful ones, are at their core land-based? That from the primary urge to survive comes the necessary reverence to do the right thing, and not vice-versa? Any parent can understand this, that at their best beliefs are just raw facts under the warming shadow of rainclouds in northern winter skies that help us to survive, no matter whose God you choose to worship.

Brandy literally grew up organically from the Land, something fewer and fewer of us have the opportunity to do. He and his colleagues successfully convinced millions that they simply could not live without those last wild places from which they sprang, which is true. More important to us now is that in applying this tree-based philosophy of “making Democracy work” to modern politics, they literally stumbled on one possible recipe to do just that, which could in fact save us, if we so choose.

“Wilderness!” you hear them say, more and more with a roll of a condescending eye about a thing within which their lives are less and less entwined, even those who now claim the mantle of Environmentalist . “That’s so Sixties!”

Well, it is just a word after all, and an expeditious one at that. But how about “democracy”? That’s just a word, too, but it describes a living organism, a land-based one, and wherever you find the Land you’ll find a different species of democracy native to that place. Here in North America, there was a vibrant form residing in human populations long before the Atlantic Ocean washed an equally-vibrant (albeit predatory) Greco-Roman form upon its shores, where they crossbred. We tend to forget that our cherished American democracy is a hybrid, a mix of the native and the non-native, a cut-bow trout swimming in the ever-more-sacred waters of an industrialized world on the very verge of polluting those waters to the last drop and then privatizing the toxic result. And then there will be no trout, no water, no democracy at all. We tend to forget that, far from being democracy’s creator, we are merely its host species, and that we neglect this symbiotic relationship at our peril.

I have allowed myself to become convinced that within the political template created by the early conservationists and the various other progressives to meld their depthless love of wild places with political realities, to get people to see the essential value of a mere word—Wilderness!--and to fight for it, are the same nuggets that could save the Land, and possibly us, from our accumulated foolishness. These stories and insights may be centered around the Northern Rockies, but it seems to me that the extreme and even violent politics we have seen here in Montana as well as throughout most of America’s rural landscapes for the last thirty years or so (the militia movement, the “Tea Party” phenomenon, the current Trump presidency) is as good a metaphor as the next for the illness that plagues us if you have the inclination to look. Old-time activism, the kind practiced in the mid-twentieth century by Big Brandy (Guy) and his son, is a pretty good recipe for fighting despair (our real enemy it seems to me) and maybe better than most given what we’re left to work with. It’s grounded and doesn’t put Jesus to sleep.

We tend to kill our prophets, or at least ignore them if their lucky, along with the core truth that burns at the heart of their misinterpreted reveries, the one about humility, about us being frogs in a slowly boiling pot of our own stew resulting in our misinterpreting that simple lesson, the one about humility. We beg our own set of questions, then, which are at heart not modern ones at all: Is it really about what the environment can do for us, or about how pretty we think things are? Or if some of us believe that sunsets are the eyes of God shining down to enlighten our path? Or if others believe that coal is the gift of that other god, the Old Testament one with the warped sense of humor? Is it even about belief at all? Is our task merely Science, then? To measure “ecosystem services” so that they can be more easily parsed up and dealt out between the various human “partners” at the negotiation “tables”? Might there be a missing ingredient in our land-based debates we’re having these days? Might it be that humankind needs as much wild country (and its evolving, resident democracies) as we can possibly nurture for the simple sake of our continued survival on this planet? Might we need to save what’s left of our remaining wilderness not as a matter of sentimentality, belief, or “ecosystem services”, but as a matter of fact?

We tend to kill our prophets, or at least ignore them if their lucky, along with the core truth that burns at the heart of their misinterpreted reveries, the one about humility, about us being frogs in a slowly boiling pot of our own stew resulting in our misinterpreting that simple lesson, the one about humility. We beg our own set of questions, then, which are at heart not modern ones at all: Is it really about what the environment can do for us, or about how pretty we think things are? Or if some of us believe that sunsets are the eyes of God shining down to enlighten our path? Or if others believe that coal is the gift of that other god, the Old Testament one with the warped sense of humor? Is it even about belief at all? Is our task merely Science, then? To measure “ecosystem services” so that they can be more easily parsed up and dealt out between the various human “partners” at the negotiation “tables”? Might there be a missing ingredient in our land-based debates we’re having these days? Might it be that humankind needs as much wild country (and its evolving, resident democracies) as we can possibly nurture for the simple sake of our continued survival on this planet? Might we need to save what’s left of our remaining wilderness not as a matter of sentimentality, belief, or “ecosystem services”, but as a matter of fact?

Our times are nothing new, and it’s never been too hard to see the mountains past the hype. Either by intent or ignorance, most of us tend to miss the forest andthe trees, and if you’ll indulge me this little bit further I’ll re-iterate that what is usually lacking in our armchair discussions about the Land is that democracy, the main ingredient in any solution of epic human concern, needs vast swaths of relatively intact ecosystems to burn in and to rejuvenate, to evolve in and to survive, and that democracy is what is lacking in the Land.

It’s something to think about, anyway.

That’s our scheme.